The importance of collaboration across organisations and jurisdictions

An important implication of the same responsibility being shared among different organisations is that inter-organisational collaboration becomes important. When a new organisation is created, people often draw attention to the need to meld together the different cultural orientations of its different components, as has happened with bringing together Test and Trace and Public Health England in the new UK Health Security Agency. This is obviously a major challenge. However, given that health hazards do not recognise administrative and political boundaries, it is just as important that a territorially based organisation be able to work with similar territorially based organisations in other jurisdictions. For example, the UK HSA provided advice to the Chief Medical Officers in UK jurisdictions on the level of the Covid-19 alert in late May 2022 (see for example).

Further, the need for inter-organisational collaboration is also relevant in relation to the role of the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, which was created in the process of setting up the UK HSA and sits within the Department of Health and Social Care. Though still under development, at present, it looks as though much of its work will be devoted to health promotion and issues such as obesity. However, it also has responsibility for air pollution. We know that exposure to the health hazards of urban air pollution has a clear social gradient. In principle, then, responsibility for such social inequalities should feed back into the scientific work of the UK HSA concerned to identify the pathways by which ill heath arises from pollution.

Understanding how public health bodies relate to other parts of government

Concern about pollution suggests another set of organisational issues, namely how public health bodies relate to other public bodies whose responsibility falls within overlapping policy areas. Because health hazards are generated from a wide variety of sources, different parts of government are involved in regulation and policy making. Thus, hazards like air pollution in the environment will fall to the responsibility of environmental protection agencies or industry regulators. A recent review of the UK government’s air quality strategy by the National Audit Office highlights breaches in implementation of air quality standards, but also identifies the key government departments responsible for implementation as Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs on the one hand and Transport on the other. As this shows, implementing policies to address a public health issue does not fall to bodies that have primary responsibility for public health.

This applies to other health hazards. Many sources of such hazards are the responsibility of a wide range of government departments, including those concerned with occupational health, traffic accidents, consumer product safety, poverty and poor housing, to name but a few. In short, once we move from policies to protect people from health hazards to policies preventing those hazards arising in the first place, we start to take in a broad range of government activity. We also see how health improvement needs to take note of what is being done, or not being done, to address the social determinants of health.

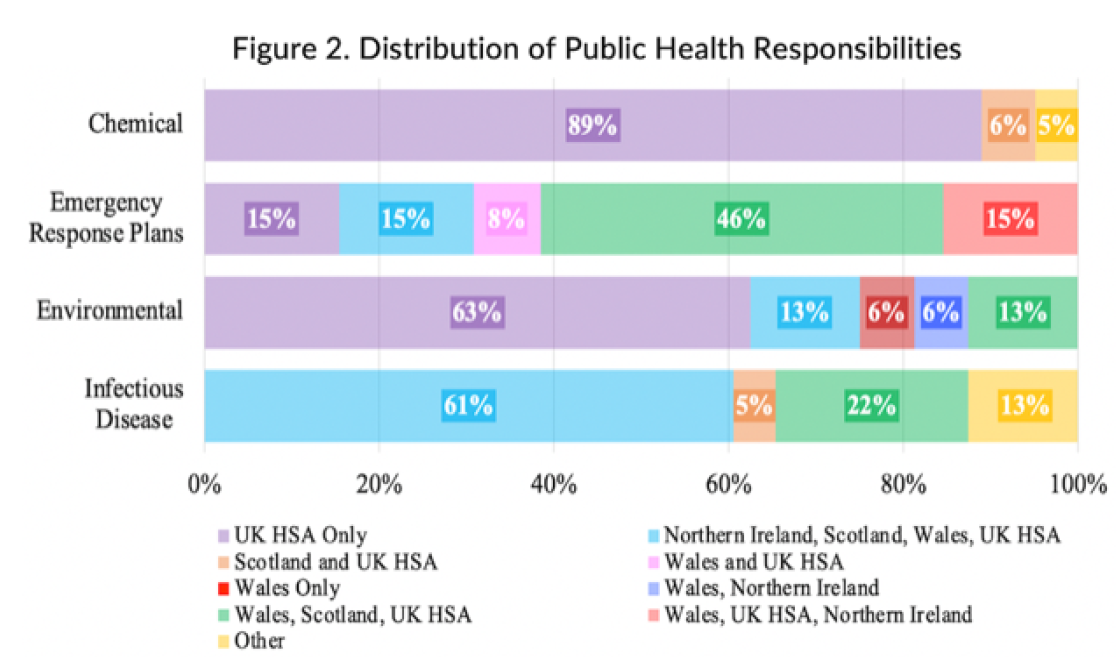

As a result of overlaps of responsibilities, in some parts of the UK a hazard will be the responsibility of the public health body, but in other parts of the UK, the responsibility, for example, of an environment agency. In Wales, for example, responsibility for drinking water falls to Public Health Wales, whereas in Scotland it falls to the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency. There is no reason to expect consistency in this respect. Different national governments will have different organisational arrangements for their various departments, and sometimes an already existing agency, like the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, will have established a track-record in a particular area of concern.

Ensuring national and local public health bodies work together

So far we have considered organisational issues at the level of national governments. However, local authorities in the UK also have public health responsibilities and these interact in important ways with responsibilities at the national level. For example, Public Health Scotland is a special health authority, but it interacts with the 14 territorially based health authorities across Scotland. In England, the importance of this central-local interaction was illustrated by the difficulties of test and trace in the Covid-19 pandemic. Although Public Health England had a good grasp of the science relating to Covid-19, it had problems scaling up its test and trace capacity to the level needed, a problem that Test and Trace, when it was established as a separate body, did not solve. The successful tracing of contacts requires local knowledge.