The editorial states: “we believe that the government is about to blunder into another major error that will cost many lives. If our political leaders fail to take swift and decisive action, they can no longer claim to be protecting the NHS.”

Suddenly all the ethical debates about balancing social needs, rights to family life, advice from epidemiologists and behavioural scientists, saving lives and livelihoods, and public health come into stark relief. It comes down to one question facing Boris Johnson and his ministers when they meet on the 16 December to review the national Covid situation. Do they decide to become as infamous as Oliver Cromwell in banning Christmas or not?

A BMA conference exploring the ethical issues generated by the Covid-19 pandemic took place just a week ago on the 8 December – so-called “V day”. I presented at the conference on ‘Justice, fairness and medical ethics seen through the lens of Covid-19’. The conference was arranged and chaired by Raanan Gillon, emeritus professor of medical ethics at Imperial College London and lifelong GP. He was the 2019-20 President of the BMA, the first ever medical ethicist to hold this office. All BMA presidents have a project and Raanan’s was to instigate and inspire a proposal to the World Medical Association to include “justice” in the Declaration of Geneva (a pledge to the humanitarian goals of medicine) and the International Code of Medical Ethics. He sought to achieve this through arranging a series of conferences and an essay competition in which entrants used ethical reasoning and theory to address a practical problem concerning justice in medicine.

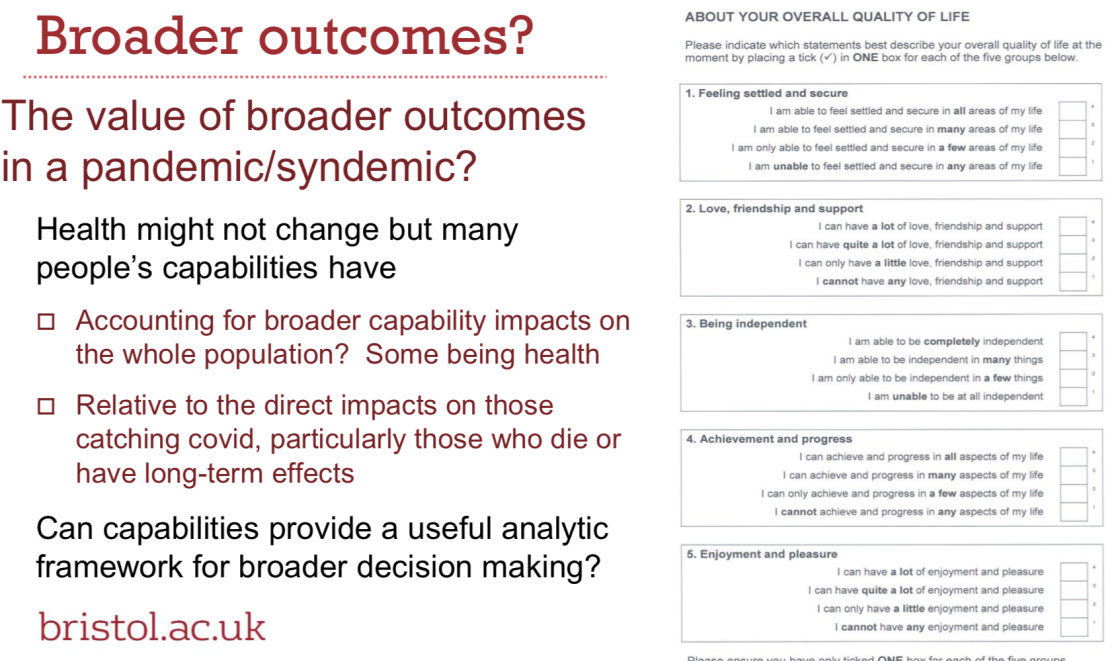

In his introduction setting out the aims of his project and this (his final) conference, Raanan referred to the seminal text Principles of Biomedical Ethics by Beauchamp and Childress, published in 1979, and their thoughts on justice in health care. The two philosophers concluded that despite outlining six main categories of theories of justice: four ‘traditional’ (utilitarian, libertarian, communitarian and egalitarian) and two newer theories, one based on capabilities and the other on actual well-being “agreement on a universalisable substantive theory of justice is ‘controversial and difficult to pin down’”. Ranaan mused that after 40 years of looking, “I have not yet found a single substantive theory of justice that is plausibly universalisable. Instead, I have made do with Aristotle’s formal, almost content-free, but probably universalisable theory, according to which equals should be treated equally and unequals unequally in proportion to the relevant inequalities – what some health economists refer to as ‘horizontal and vertical justice or equity’.”

However, Raanan continued: “Two reflections about justice may provide some element of relief. The first is another from Aristotle: ethics is not an exact science, it is a ‘for the most part’ affair, including concerns for likelihoods and probabilities rather than certainties. […] The second reflection is from Immanuel Kant, about the importance of our mysterious capacity for judgment when values and principles conflict. Unless you believe that there’s only one over-riding moral principle, or where moral conflicts arise, there’s a system of rigidly prioritised values or principles which require an algorithm rather than moral judgment, then you will, as a moral agent be required to exercise moral judgment about which moral rules to apply”.

The conference first explored the tension in medical ethics between what is best for the individual patient and for the health of the population. I was the first speaker taking the population health perspective. My talk emphasised the need to treat all patients (not only Covid-19 patients) equally (see my previous blog) and that some form of prioritisation is inevitable, going on to describe our ARC research on how to do this fairly, with an emphasis on public involvement.

I discussed the results of a recent King’s College London / Ipsos MORI public event exploring how to achieve the best outcomes from intensive care units in the second wave. The public were very clear that old age should not be a criteria for prioritisation and that the most vulnerable should be prioritised. I explored the epidemiological and political debate surrounding the opposite approaches to controlling the virus (blanket versus shielding approaches) and finally the ethics of who gets the vaccine. Subsequently I have sent a letter to the BMJ commenting on the deviation from the prioritisation list on the first day of roll out!

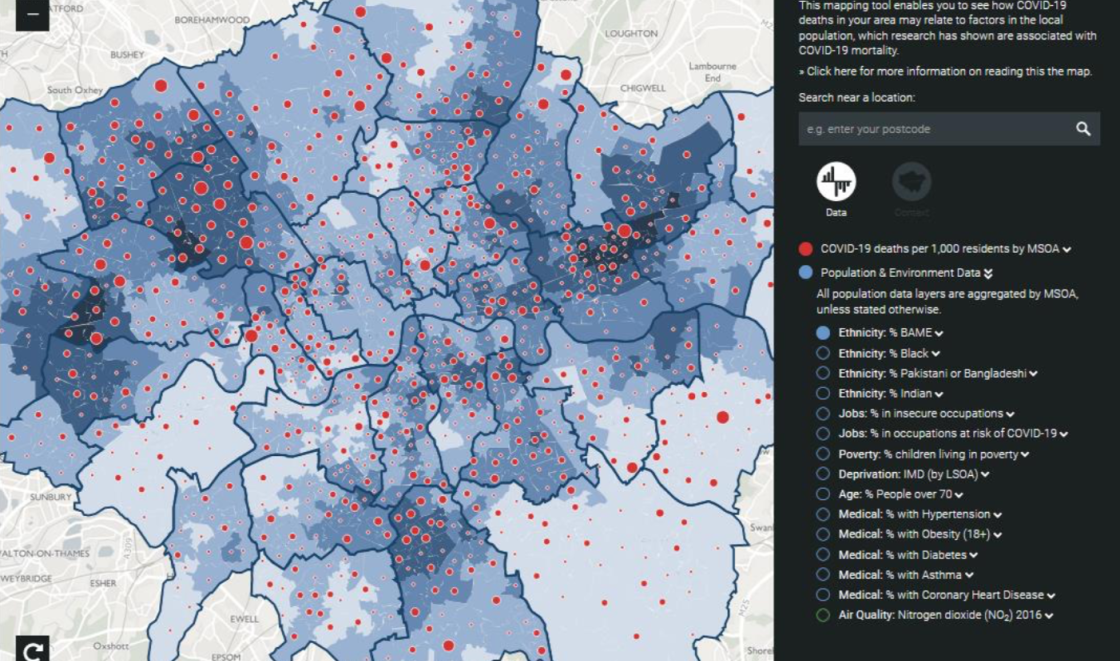

Iona Heath, Past President of the Royal College of General Practitioners gave the individual patient perspective and it was revealing how similar our approaches were. She began by emphasising the importance of the individual, quoting Kant’s argument that the rightness of an action depends upon treating a person as an end in themselves rather than a means to some consequence. Ioan also quoted Sven Lindqvist’s words in his 1990 book Desert Divers on the importance of the personal – “Not until the vast wealth of high-flown rhetoric has been cashed into the ordinary small change of a household do we see what it really entails - for me, for you, for all of us.” However, her main thesis was on the impact of socio-economic determinants of health and she presented slides showing the Covid-19 hot spots in London and their alignment with indicators of overcrowding and Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities (pictured below).