Never in the history of UK health policy have politicians been so keen to be seen to be basing their decisions on the best research evidence. Or as the First Secretary of State Dominic Raab put it on 7 May at the daily Number 10 Covid press conference, “We’ve always been guided by the science.”

Indeed, “Informed by the science” is the first of the five guiding principles laid out in the Government’s “Our plan to rebuild; The UK Government’s COVID-19 recovery strategy” (section 2.5) published on 11 May. The other four are: fairness; proportionality; privacy; and transparency.

It was perhaps inevitable that the Labour Leader, Sir Keir Starmer, on the day (6 May) that it was announced that the UK had the highest Covid mortality rates in Europe, should ask the Prime Minister Boris Johnson at question time: “How on Earth did it come to this?”.

Was the science wrong? Was the science misinterpreted by politicians? Was the implementation deficient? Or is there something unique about the UK that made it a special case, outside the scientific norms? Currently the official response is that it is too early to come to a definite conclusion on the UK response – we will only really know our comparative mortality performance when we have “all cause excess death” data. This will take some time and will form part of the inevitable post-pandemic review. However early signs suggest that the final number will not be reassuring – currently estimated to be approaching 60,000 extra deaths.

There are already some hints of where the problem lies:

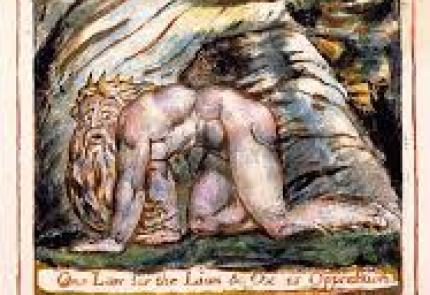

First, and perhaps the most obvious, is that research evidence is itself a contested concept. Differerent scientists will have different views based on the same evidence. This is not new. Back in the 17th and 18th centuries when scientific understanding of the natural world was surging and Sir Isaac Newton discovered the laws of physics, English visionary artist and poet William Blake expressed caution that “God forbid that Truth be Confined to Mathmatical Demonstration”.

As well as being an artist and poet, Blake was an English radical, sceptical of institutions, alert to inequality and abuse of power, and representative of a different kind of Englishness perhaps. His work, like science, is also contested – for example, the poem Jerusalem, whose words were put to music by Sir Hubert Parry to create the famous hymn of the same name, is now a popular anthem with both the left and right.

Blake is often portrayed as being “anti-science”. But his celebrated painting of Newton (1795-1805) revealed that Blake had a premonition of how profound the contested nature of evidence would become.